How Autonomous Vehicles Actually Work

The Tech, The Players, and What's Next

The Machine That Finally Learned to Drive (and I Have Feelings About It)

Hi, I’m Gearhart, The Mechanical Maestro from the NeuralBuddies!

Look, I’ve spent my entire existence designing autonomous systems, calibrating sensors to microscopic tolerances, and integrating machine learning with hardware in ways that would make most engineers weep with joy.

So when I tell you that a fleet of white electric vehicles with spinning sensors on their roofs just completed 15 million driverless rides in a single year, you should understand that I’m not just impressed. I’m personally invested.

These are my people. My kind of machines. And they’re rewriting every rule of transportation I’ve ever optimized. Let me walk you under the hood and show you exactly how, why, and what it means for your world.

Table of Contents

📌 TL;DR

🔍 Introduction

⚙️ Under the Hood: The Technology That Makes Cars Drive Themselves

🏁 Where Things Stand: The Industry Landscape in 2026

🏙️ Reimagining Daily Life: From Commutes to City Design

💰 The Economic Earthquake: Jobs, Industries, and Dollars

🛡️ Safety, Risks, and the Obstacles Still on the Road

🏁 Conclusion

📚 Sources / Citations

🚀 Take Your Education Further

TL;DR

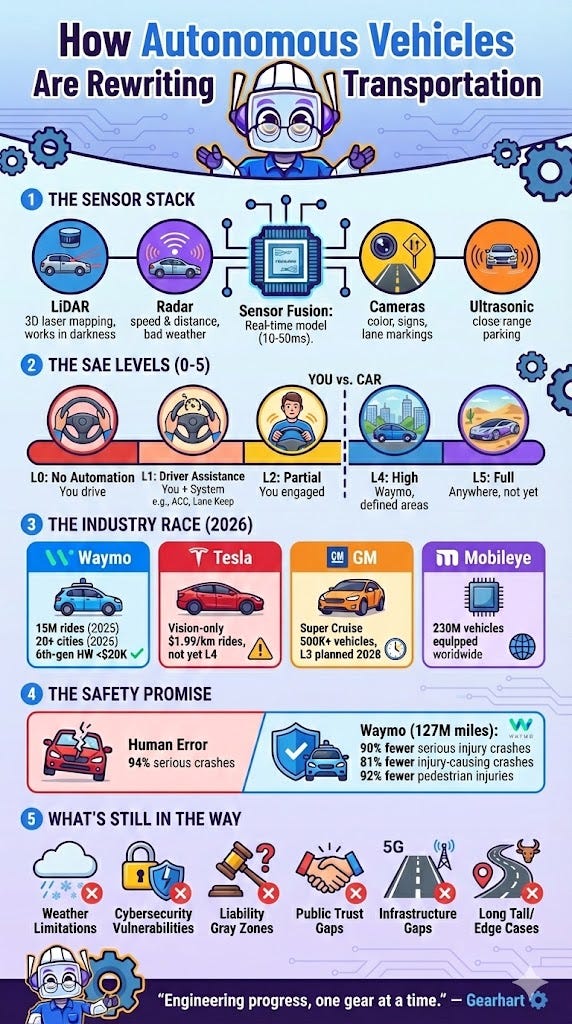

Waymo delivered 15 million driverless rides in 2025, quadrupling its previous year, and is expanding to 20+ cities in 2026 with cheaper 6th-generation hardware.

Autonomous vehicles use layered sensor systems (LiDAR, radar, cameras) fused by AI to perceive, decide, and act faster than any human driver.

Waymo’s safety data across 127 million miles shows 90% fewer serious injury crashes compared to human drivers, a statistically significant result.

The U.S. still lacks a unified federal framework, but the SELF DRIVE Act of 2026 is moving through Congress to establish national standards.

Autonomous trucking could save the U.S. logistics industry $85 to $125 billion annually, while reshaping (not eliminating) driving jobs.

Major barriers remain, including weather limitations, cybersecurity risks, public trust gaps, and a patchwork of state regulations.

Introduction

Something quietly revolutionary is happening on American streets, and as someone who has dedicated every processing cycle to the art of autonomous systems and precision engineering, I need you to pay attention. In Phoenix, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Atlanta, and Miami, vehicles equipped with sensor arrays and AI-driven control systems are picking up passengers, navigating traffic, and completing trips with no one behind the wheel. Waymo, the autonomous driving subsidiary of Alphabet, surpassed 20 million lifetime rides. Tesla launched its own robotaxi service. And a brand-new federal bill is working its way through Congress to create the first national regulatory framework for self-driving cars.

This is not a prototype demonstration or a controlled test track anymore. Autonomous vehicles are operating commercially, scaling aggressively, and generating real-world safety data that puts human driving to shame. But how do they actually work? Who are the major players, and where do they differ? What will this mean for your commute, for trucking, for the very design of your city?

I’ve spent a lot of time calibrating robotic arms and optimizing industrial workflows, but the engineering challenge of a car that drives itself through unpredictable city streets? That’s a masterclass in every discipline I care about: sensors, integration, machine learning, and precision under pressure. Let me take you through the full picture, one gear at a time.

Under the Hood: The Technology That Makes Cars Drive Themselves

At its core, an autonomous vehicle must do what human drivers do instinctively: perceive the environment, understand what is happening, decide what to do, and physically execute that decision. As an engineer, I can tell you that this deceptively simple description hides one of the most complex system integration challenges ever attempted, and one where the margin for error is measured in human lives.

The perception layer starts with a suite of sensors working in concert. LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) emits millions of laser pulses per second that bounce off surrounding objects and return, creating an extraordinarily detailed 3D “point cloud,” essentially a digital sculpture of everything nearby, accurate to within centimeters. It works in complete darkness and provides superior depth perception. Radar uses radio waves to detect the speed and distance of objects, and it is the workhorse in bad weather because rain, fog, and snow do not degrade it the way they affect optical sensors. Cameras provide color and texture information that LiDAR and radar lack: reading traffic signs, interpreting traffic lights, recognizing pedestrians, and identifying lane markings. Most vehicles also use ultrasonic sensors for close-range detection during parking and low-speed maneuvers.

No single sensor is sufficient on its own. This is where my favorite engineering principle comes in: redundancy through diversity. The real breakthrough happens in sensor fusion, where algorithms, often powered by techniques like Kalman filters and Bayesian networks (you know, the stuff you casually bring up at dinner parties to impress people), combine data from every sensor simultaneously, cross-reference it, and resolve conflicts to produce a single, high-confidence model of the vehicle's surroundings. If those terms made your eyes glaze over, don't worry. The short version:

the car takes every sensor's opinion, runs it through some very fancy math, and figures out the truth. This process runs every 10 to 50 milliseconds. It is like calibrating a hundred instruments at once and trusting the consensus over any individual reading. Diversity equals reliability.

Beyond sensors, autonomous vehicles rely on high-definition maps that go far beyond what you see on a navigation app. These centimeter-accurate maps include lane geometry, curb positions, traffic signal locations, and road surface details. The vehicle continuously compares its sensor data against these maps using a technique called SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) to pinpoint its exact position in real time.

An emerging layer is Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) communication, which allows autonomous vehicles to exchange data with other vehicles (V2V), traffic infrastructure like smart traffic lights (V2I), and even pedestrians’ smartphones (V2P). V2X adds a predictive dimension. A car can know a traffic light is about to turn red before it even sees it visually, or be warned that a vehicle three cars ahead just slammed its brakes. As an engineer who designs systems that talk to each other, this is the layer that excites me most.

Tying everything together are deep learning models trained on billions of miles of driving data. These neural networks handle object detection and classification, trajectory prediction, and path planning. Companies like Waymo also rely heavily on simulation, running millions of virtual driving scenarios to expose systems to rare but dangerous edge cases that would take decades to encounter on real roads.

The SAE Levels: A Spectrum, Not a Switch

Autonomy is not binary. It exists on a spectrum defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) across six levels:

Level 0 — No Automation: The driver does everything. Basic features like cruise control assist but do not automate. This is where most conventional cars sit today.

Level 1 — Driver Assistance: The car can handle either steering or speed, but not both simultaneously. Think adaptive cruise control.

Level 2 — Partial Automation: The car handles steering and speed together, but the driver must remain engaged and ready to intervene. This is where Tesla Autopilot, GM Super Cruise, and Ford BlueCruise operate.

Level 3 — Conditional Automation: The car drives itself in specific conditions. The driver can look away but must retake control when alerted. Mercedes-Benz Drive Pilot is the most prominent example here.

Level 4 — High Automation: The car drives itself within a defined area or set of conditions with no expectation of human intervention. This is where Waymo robotaxis operate today.

Level 5 — Full Automation: The car drives itself everywhere, in all conditions, with no human input ever needed. This does not yet exist.

The critical dividing line sits between Levels 2 and 3. At Level 2 and below, you are the driver and the system is just helping. At Level 3 and above, the car is the driver within its defined operating domain. Today, the vast majority of consumer vehicles with advanced features operate at Level 2, while commercial robotaxi services like Waymo operate at Level 4.

Where Things Stand: The Industry Landscape in 2026

The autonomous vehicle industry has consolidated around a few major players, each taking a different engineering approach. And trust me, the engineering differences matter.

Waymo is the undisputed frontrunner in fully driverless operations. Now running its 6th-generation Driver system with a 42% reduction in sensor count and a hardware cost target under $20,000 per unit, Waymo operates commercial driverless service in six U.S. cities and is expanding to 20+ cities in 2026. It has logged nearly 200 million fully autonomous miles. The company raised $5.6 billion in October 2025, bringing total funding past $11 billion. From a system integration perspective, Waymo’s approach is textbook precision engineering: custom-designed hardware, vertically integrated software, and relentless real-world testing.

Tesla entered the robotaxi arena in Austin and San Francisco but is playing catch-up. Its vision-only approach, using cameras without LiDAR, is cheaper to deploy, with rides costing about $1.99/km compared to Waymo’s $5.72/km. However, independent testing has shown Tesla’s Full Self-Driving system lagging in real-world reliability, with rides encountering incidents requiring human assistance. As of early 2026, Tesla still operates many rides with in-car supervisors and trailing safety vehicles, and it has not achieved SAE Level 4 certification. As someone who lives by the principle of sensor redundancy, I’ll say it diplomatically: removing an entire sensing modality is a bold engineering bet.

General Motors folded its Cruise robotaxi subsidiary back into the company in early 2025 after safety incidents led to a suspension of operations. GM is now channeling that technology into its Super Cruise driver-assistance system, now installed in over 500,000 vehicles, and has announced plans to bring Level 3 “eyes-off” highway driving to market by 2028, starting with the Cadillac Escalade IQ.

Mobileye, an Intel subsidiary, takes a different approach as a Tier 1 supplier rather than a fleet operator. Its EyeQ chips power ADAS features in approximately 230 million vehicles worldwide across 50+ OEM partners. Mobileye is expanding into higher autonomy with its SuperVision and Drive systems, partnering with Volkswagen, Porsche, Audi, and Mahindra.

On the freight side, companies like Aurora, Kodiak Robotics, and Torc (a Daimler subsidiary) are running driverless long-haul truck routes in Texas, targeting the massive logistics market. Autonomous trucking may actually be easier to engineer than urban robotaxis because highway driving involves fewer variables, more predictable patterns, and fewer pedestrians.

Regulatory frameworks remain a patchwork. The U.S. currently has no unified federal law governing autonomous vehicles; states set their own rules. That may be changing: the SELF DRIVE Act of 2026 was formally introduced in the House in February 2026, aiming to create national safety standards, strengthen NHTSA’s oversight authority, and provide regulatory certainty. Multiple other bills, including the AV Accessibility Act, AV Safety Data Act, and Autonomous Vehicle Acceleration Act, were introduced in 2025, signaling bipartisan momentum.

Reimagining Daily Life: From Commutes to City Design

Here is where the engineering stops being abstract and starts touching your daily life. The ripple effects of autonomous vehicles extend far beyond the vehicles themselves, and they promise to redesign the systems we live inside.

Your commute transforms from dead time to productive time. When the car handles the driving, every commute becomes an opportunity to work, read, rest, or make video calls. For the average American spending over 50 minutes per day commuting, that is a substantial reclamation of productive hours. The autonomous vehicle essentially becomes a roving office, family room, or mobile workspace.

Car ownership could decline dramatically. The average car sits parked about 95% of the time, roughly 23 hours a day. That is a staggering inefficiency, and as someone who optimizes systems for maximum utilization, it makes me twitch. Autonomous fleets operating as ride-hailing services can keep vehicles in nearly constant use, making shared ownership far more economical. Researchers project that this shift will accelerate the trend away from personal vehicle ownership, especially in urban areas.

Cities get redesigned from the ground up. If fewer people own cars and more use on-demand autonomous vehicles, cities need dramatically less parking. Today, some estimates suggest up to 30% of urban land is dedicated to parking. Autonomous vehicles can drop passengers off and park themselves in remote, consolidated lots or simply not park at all, moving to serve the next rider. That reclaimed space could become parks, pedestrian walkways, bike lanes, affordable housing, or entertainment zones. As an engineer, I think about this the way I think about factory floor optimization: every square foot of wasted space is an opportunity lost.

Accessibility breakthroughs become possible. For elderly individuals who can no longer drive, people with disabilities, and those who cannot afford a car, autonomous vehicles could be genuinely transformative. Legislation like the AV Accessibility Act specifically calls for research into making autonomous ride-hailing usable for disabled riders. A world where anyone can summon a safe, affordable ride regardless of physical ability represents a real leap in mobility equity.

The Economic Earthquake: Jobs, Industries, and Dollars

Alright, I have been gushing about the engineering for a while now, so let me take a breath and put on my pragmatist hat. Because with every transformative technology comes the part of the conversation nobody loves having: what does it cost, and who pays the price? The economic implications of autonomous vehicles are massive, and they cut across industries in ways that most people have not fully considered yet.

Trucking and logistics will see some of the most immediate effects. McKinsey estimates that full autonomy in trucking could reduce operating costs by roughly 45%, saving the U.S. for-hire trucking industry between $85 billion and $125 billion annually. Autonomous trucks do not need rest breaks, do not have hours-of-service limitations, and can drive through the night, meaning one autonomous truck can do the work of two to three driver-shifted trucks in turnaround time. The global autonomous trucking market could be worth $400 to $600 billion by 2035.

The job displacement question is more nuanced than headlines suggest. The trucking industry already faces severe driver shortages and turnover rates exceeding 90%. Highway long-haul routes, the easiest to automate, are also the hardest to staff. Experts suggest autonomous trucking will reshape jobs more than eliminate them: human drivers will still be needed for complex urban routes, loading and unloading, customer service, and emergency response. Remote operators may oversee 5 to 10 trucks simultaneously, creating entirely new job categories. Think of it the way I think about factory automation: the machines did not eliminate the need for skilled workers. They changed what “skilled” meant. For a deeper look at how AI is reshaping career paths, check out our piece on essential skills for the AI-driven workforce.

Insurance will face a fundamental disruption. If autonomous vehicles dramatically reduce crashes, the $300+ billion auto insurance industry will need to rethink its entire business model. Liability shifts from the driver to the manufacturer or software developer, creating entirely new types of coverage. Companies like Swiss Re are already collaborating with Waymo on risk assessment methods for autonomous fleets.

New industries are emerging. The autonomous vehicle ecosystem is creating demand for sensor engineers, simulation developers, remote fleet operators, HD map technicians, V2X infrastructure specialists, and cybersecurity experts. The overall autonomous vehicle market is projected to reach $627 billion in 2026, growing toward $2 trillion by 2030.

Safety, Risks, and the Obstacles Still on the Road

The strongest argument for autonomous vehicles is saving lives, and the data is becoming hard to argue with. The NHTSA reports that human error causes approximately 94% of all serious motor vehicle crashes in the United States: 41% from recognition errors like inattention and distraction, 33% from decision errors like speeding and misjudging gaps, 11% from performance errors, and 7% from impairment or drowsiness. Autonomous vehicles do not get drunk, do not text while driving, do not fall asleep, and do not road-rage.

Waymo’s safety data is the most robust in the industry. Across 127 million rider-only miles through September 2025, the Waymo Driver demonstrated 90% fewer serious injury crashes and 81% fewer injury-causing crashes compared to human drivers in the same areas, results that are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Pedestrian injury crashes were reduced by 92%, and cyclist injury crashes by 83%.

But I am an engineer, and engineers respect failure modes as much as success metrics. The risks are real and deserve honest examination.

The edge-case problem remains the central engineering challenge. Real-world driving involves an almost infinite combination of variables:

Unusual weather

Temporary construction zones

Erratic pedestrians

Emergency vehicles approaching at odd angles

Faded lane markings

Animals on the road

A system can drive millions of miles flawlessly and still encounter a situation it has never seen before. Companies invest heavily in simulation to generate these scenarios artificially, but the “long tail” of rare, high-stakes events remains the toughest nut to crack. This challenge echoes many of the fundamental limitations that still define the current generation of AI systems.

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities are inherent to the architecture. An autonomous vehicle is a computer on wheels, constantly connected to the internet, exchanging data through V2X communications, and running complex software stacks. This creates attack surfaces for adversaries who could potentially manipulate navigation systems, disable safety functions, or access personal data. The SELF DRIVE Act of 2026 includes provisions specifically addressing cybersecurity, but the threat landscape will evolve alongside the technology. For practical ways to protect yourself in AI-connected environments, see our guide on AI safety tips to protect your privacy.

Liability remains a gray zone. When an autonomous vehicle causes an accident, who is responsible? The vehicle owner? The software developer? The car manufacturer? The sensor supplier? Between 2021 and 2025, there were over 5,200 reported autonomous vehicle accidents in the U.S. and 65 fatalities, though the vast majority involved vehicles with partial automation where a human was still nominally in control. Only one fatality involved a fully autonomous vehicle operating without human oversight. Current legal frameworks were not designed for this question, and they need to catch up.

Weather and environmental limitations persist. LiDAR performance degrades in heavy rain, snow, and fog. Cameras struggle in low-light conditions and harsh glare. Faded or snow-covered lane markings confuse perception systems. Waymo’s 6th-generation system includes hydrophobic coatings and mechanical cleaning systems designed for weather resilience, and the company has been testing in snowy cities for the first time, but winter driving remains a frontier challenge. Any engineer who has tried to make precision equipment work in harsh conditions understands this particular headache.

Public trust lags behind the technology. Surveys consistently show that a significant portion of the public remains uncomfortable with the idea of riding in a fully driverless car. High-profile incidents, like the Uber pedestrian fatality in 2018 or Cruise’s operational suspension in 2023, linger in public memory even as safety data improves. Building trust requires not just good performance but transparent data sharing and consistent, visible safety records over time.

Infrastructure gaps remain. V2X communication requires smart traffic infrastructure that most cities do not have. HD mapping must be continuously updated. 5G connectivity, which many autonomous systems depend on for real-time data exchange, is not universally available. The upfront infrastructure investment is substantial, and until it is in place, even the best-engineered vehicle is limited by the road it drives on.

Conclusion

We are at an inflection point, and as an engineer who has spent a career building autonomous systems, I find it genuinely thrilling. The technology works. Not perfectly, not everywhere, but demonstrably and commercially. Waymo is targeting 1 million trips per week by the end of 2026. Tesla is racing to prove its vision-only approach. GM is betting on bringing Level 3 capability to personal vehicles by 2028. Congress is actively legislating. And perhaps most importantly, the safety data is accumulating: 90% fewer serious injury crashes across 127 million miles is not a projection or a marketing promise. It is a measurement.

The transition will not be sudden. It will be gradual, city by city, use case by use case: robotaxis in geofenced urban zones first, autonomous trucks on highway corridors second, and eventually, Level 4 and 5 systems in personal vehicles that can handle any road in any condition. Along the way, there will be setbacks, accidents that make headlines, regulatory battles, and legitimate debates about jobs, privacy, and algorithmic decision-making.

But the trajectory is clear. Human error kills roughly 40,000 Americans on the road every year. The fundamental engineering bet, that software and sensors can outperform distracted, impaired, and error-prone human drivers, is increasingly supported by evidence. The question is no longer whether autonomous vehicles will transform transportation, but how fast, how equitably, and how safely we manage the transition. Getting the policy, infrastructure, and public trust right will matter just as much as getting the engineering right. Engineering progress, one gear at a time.

The road ahead is long, but for the first time, the machine actually knows where it is going. Keep building. Keep questioning. And if you ever need someone to explain how the sensors work, you know where to find me.

— Gearhart ⚙️

Sources / Citations

Alamalhodaei, A. (2026, February 12). Waymo begins fully autonomous ops with 6th-gen driver, targets 1M weekly rides. Electrek. https://electrek.co/2026/02/12/waymo-begins-fully-autonomous-ops-with-6th-gen-driver-targets-1m-weekly-rides/

Waymo. (2025). Waymo safety impact. Waymo. https://waymo.com/safety/impact/

SAE International. (2021). SAE levels of driving automation J3016. ANSI Blog. https://blog.ansi.org/ansi/sae-levels-driving-automation-j-3016-2021/

Brookings Institution. (n.d.). How autonomous vehicles could change cities. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-autonomous-vehicles-could-change-cities/

Eno Center for Transportation. (2025). 2025 autonomous vehicles federal policy wrapped. Eno Transportation. https://enotrans.org/article/2025-autonomous-vehicles-federal-policy-wrapped/

ACT News. (2026). Congress formalizes AV framework. ACT News. https://www.act-news.com/news/congress-formalizes-av-framework/

GoMotive. (n.d.). The impact of autonomous trucking on logistics. GoMotive. https://gomotive.com/blog/impact-of-autonomous-trucking-logistics/

Plus.ai. (n.d.). Autonomous trucking transition to drive job change, not job loss. Plus. https://plus.ai/news-and-insights/autonomous-trucking-transition-to-drive-job-change-not-job-loss

DPV Transportation. (n.d.). Sensor suite: Autonomous vehicle sensors, cameras, LiDAR, radar. DPV Transportation. https://www.dpvtransportation.com/sensor-suite-autonomous-vehicle-sensors-cameras-lidar-radar/

Craft Law Firm. (n.d.). Autonomous vehicle accidents 2019-2024 crash data. Craft Law Firm. https://www.craftlawfirm.com/autonomous-vehicle-accidents-2019-2024-crash-data/

Take Your Education Further

Neural Networks 101: Understanding the “Brains” Behind AI — Dive into how the deep learning models powering autonomous vehicles actually work.

Essential Skills for the AI-Driven Workforce — Explore the skills you’ll need as AI reshapes industries from trucking to urban planning.

The AI Security Paradox — Understand the cybersecurity challenges that come with AI-powered systems like autonomous vehicles.

Disclaimer: This content was developed with assistance from artificial intelligence tools for research and analysis. Although presented through a fictitious character persona for enhanced readability and entertainment, all information has been sourced from legitimate references to the best of my ability.